Olive trees in December, the road between Bethlehem and Jerusalem. Photo: Reed Miller.

Olive Harvest in the Valley of Gehenna, Jerusalem. Photo: Henri Gourinard

In the photo, you can see a father and his children spreading tarps at the base of the tree. While the father uses a stick to tap the branches, one of his children climbs the tree to shake the olives, causing them to fall onto the tarps. Although it’s true that the way of harvesting olives hasn’t changed much over the centuries, modern techniques have revolutionized the oil extraction process.

To get an idea of the ancient pressing methods, one can simply visit an archaeological site. The biblical city of Maresha serves as a good example. It is located in the foothills of the Shephelah, a border area between the Judean mountains and the Philistine coast. During the Hellenistic period (4th-1st centuries BC), the city specialized in the production and trade of olive oil.

The surroundings of Maresha in springtime. Photo: Henri Gourinard

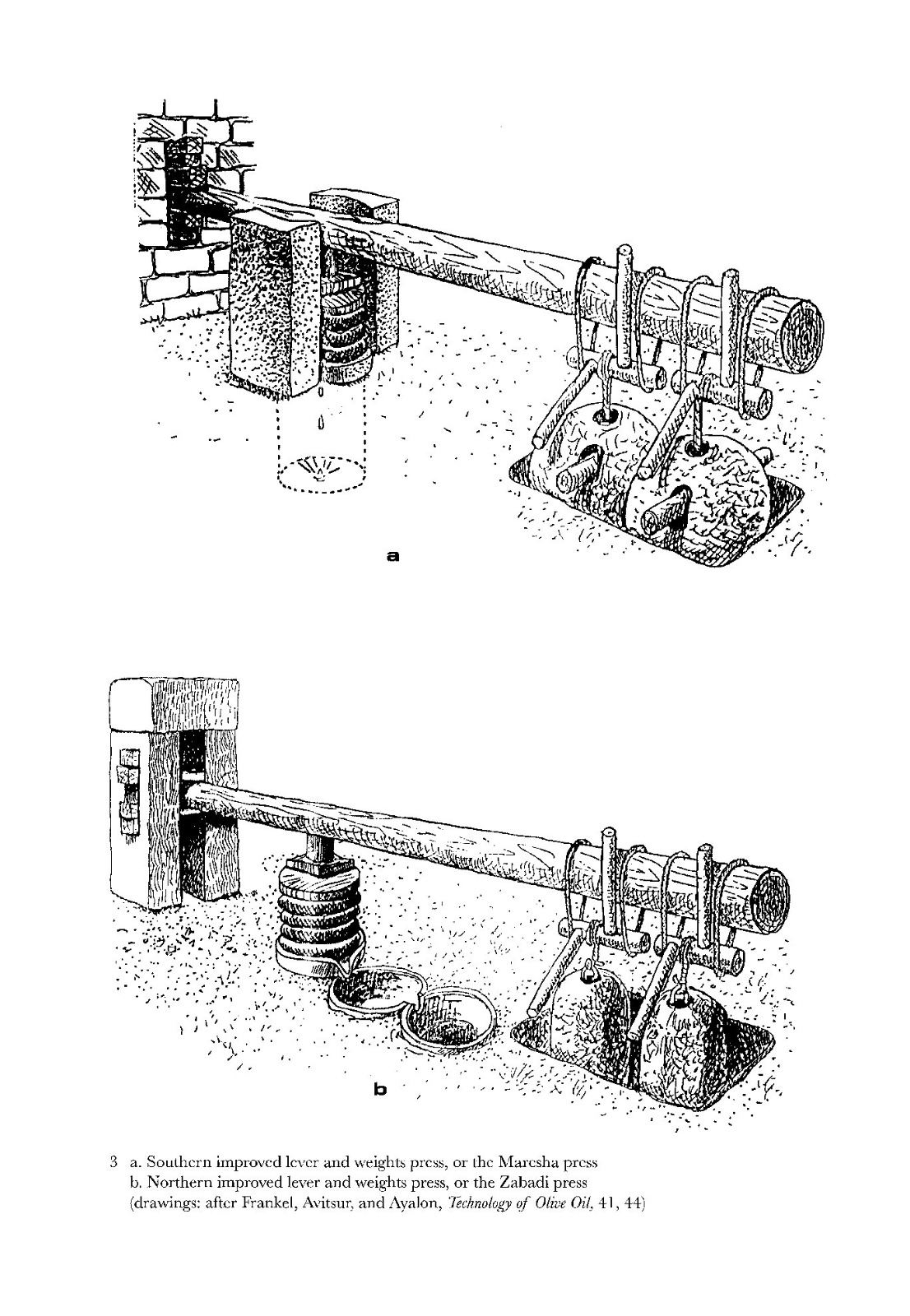

The twenty olive presses that archaeologists found in caves that had been carved into the chalk in Maresha allowed the city to produce the equivalent of 270 tons of olive oil per year, primarily intended for export to Egypt. In one of these caves, you can admire the ingenuity of such agricultural facilities.

Archaeologists have reconstructed an olive press to show visitors the two phases of the oil extraction process. The first phase takes place in the olive mill. The olives are poured into a large stone basin where a millstone attached to a vertical shaft and powered by a donkey (or in biblical times sometimes slaves) will crush them. The resulting paste is collected in wicker baskets.

Example of an olive mill (left) and a press (right), Maresha (Israel). Photo: Henri Gourinard

The press at Maresa. Drawing: Rafael Frankel, “Introduction” in Etan Ayalon, Rafael Frankel, Amos Kloner (eds.), Oil and Wine Presses in Israel from the Hellenistic, Roman and Byzantine Periods, BAR (2009), p. 16.

Subsequently, the baskets are stacked under a large beam. One end of the beam is embedded in the wall of the room. At the other end, stone weights were hung. The weight of the beam compresses the baskets. The oil that filters through the pores of the baskets falls into basins carved into the floor.

At the foot of the Mount of Olives, the Garden of Gethsemane likely took its name from an olive press that was there. This is the Hebrew meaning of the name of the garden where Jesus used to retreat with his disciples (Jn 18,1-3).

By Henri Gourinard

Olive trees in the Kidron Valley. Photo: Henri Gourinard