The word “prophet” comes from the Greek profetes, derived from the verb pro-femi, meaning “to speak forth” or “to speak on behalf of another,” especially on behalf of the divine. This is a faithful translation of the Hebrew term nabí (plural nebiim), likely connected to a root that means “to call” or “to proclaim.” A nabí, therefore, is “the called one” or “the one who announces,” that is, the messenger of God’s word.

The books of the New Testament repeatedly affirm that the hope proclaimed, and the salvation announced by the prophets have been fulfilled in Jesus—through His Person, His actions, and His words. Saint Matthew openly declares this: “But all this has come to pass that the writings of the prophets may be fulfilled“ (Matthew 26:56). The Gospels and the Apostolic Letters pay great attention to what the prophets said, constantly highlighting that their oracles have come to fulfillment.

Nathan and David by Matthias Scheits

For this reason, Christians of all times have an interest in learning about these figures, frequently mentioned at various points in biblical history. They are not distant characters or lost voices crying out from a remote past. God has spoken through their actions and words, and their message remains perpetually relevant.

Elijah with the Angel by Juan de Valdés Leal

In this discussion, we will focus on the earliest biblical prophets—those mentioned in some biblical texts but whose prophecies or oracles have not been preserved in written form. Later, we will address the writing prophets as well.

The earliest prophets of Israel were individuals belonging to groups associated with places of worship, occasionally referenced in the sacred texts. Mentions of these figures refer to activities with external manifestations partially analogous to those of the Canaanite “prophets” in the region, who would fall into an intense and exuberant spiritual state, accompanied by shouting, dancing, and music. However, unlike the latter, these prophets proclaimed faith in the one God of Israel.

They often lived together and relied on alms for their sustenance. These groups are referred to in the Bible as bene nabi or bene nebiim, that is, “sons of a prophet” or “of prophets.” Their lifestyle was very austere, typically wearing a hair mantle over a tunic tied with a leather belt. Sometimes, they bore marks on their foreheads or scars from wounds inflicted during their trances.

Prophet Elijah with the prophets of Baal by Juan de Valdés Leal

At the beginning of the monarchy, members of these prophetic groups also reached the royal court, serving as advisors to kings. Some were chosen by the Lord to guide monarchs regarding the divine will or to help them recognize their sins and seek penance. Among them, Samuel, Nathan, and Gad played significant roles in the accession of Saul and David to the throne and during David’s reign.

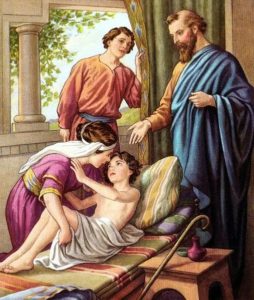

Elisha Raising Shunammites Son

Later, during the reign of Ahab of Israel, Elijah and Elisha appear on the scene. Both carried out their mission in the northern kingdom during the 9th century BC. The books of Kings emphasize that their words, like those of all true prophets and men of God, come to pass precisely and inexorably, even if much time has elapsed since they were spoken. This narrative approach underscores the certainty that the word of God, pronounced through the prophets, effectively guides and directs the history of Israel with divine power.

By Francisco Varo, priest