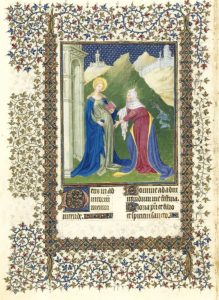

By the end of the Middle Ages, illuminations in the books of hours depicted the Visitation scene following very conventional models. The Virgin Mary is cloaked in a sky-blue mantle; her cousin Elizabeth in a purple robe or mantle, with a white veil. The encounter takes place in front of a house. In some illuminations, Zechariah appears peering from the doorway and witnessing the scene, just as Sarah peeked from the threshold of the tent while Abraham received the three angels. Generally, Mary and Elizabeth greet each other with an embrace. Elizabeth rests her hand on Mary’s belly to feel the first movements of the baby Jesus. In the background, there is a stylized village and always, mountains.

Les Belles Heures de Jean de France, Heures de la Vierge, Fol. 42

Livre d’heures d’Agnès le Dieu, Fol. 49r

In painting so many details, the artists aimed to compensate for the scarce information provided by the Gospel of Saint Luke regarding the exact location of the encounter between Mary and Elizabeth, and the birth of Saint John the Baptist. Saint Luke (1:39-40) states:

Exsurgens autem Maria in diebus illis, abiit in montana cum festinatione, in civitatem Juda: et intravit in domum Zachariæ, et salutavit Elisabeth.

“During those days Mary set out and traveled to the hill country in haste to a town of Judah, where she entered the house of Zechariah and greeted Elizabeth.”

Mosaic on the façade of the Church of the Visitation

The Vulgate, which inspired these artists, indicates that the house of Zechariah (and Elizabeth) was located in a “city” in the mountains of Judah.

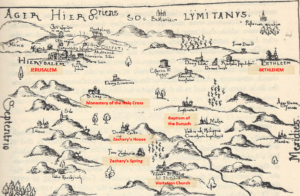

Indeed, pilgrims, for centuries, used to travel a pilgrimage route that, starting in Bethlehem, passed by the place where Philip baptized the Ethiopian eunuch, the “House of Zechariah,” and the monastery of the Holy Cross.

Ager Hierosolymitanus, Mapa de Jerusalén y alrededores por S. Werro (1581)

Thanks to the distance indications recorded by pilgrims in their diaries, we can precisely locate the “House of Zechariah” that they visited. Most accounts point to a distance of about four miles from Jerusalem. These data corroborate a tradition that, since the time of the Crusades, places the birthplace of the Baptist in the village of Ein Karem. However, it is not until the end of the 15th century that the name Ein Karem appears in the sources.

The first to mention the name Ein Karem is Francesco Suriano. He was Guardian of the Franciscan convent of Mount Sion – a title equivalent to the current Custodian of the Holy Land. In his Treatise on the Holy Land, he lists the indulgences that pilgrims can earn at the shrines dedicated to the Baptist: the church where Saint John the Baptist was born, the house of Zechariah where the Virgin visited Saint Elizabeth and recited the Magnificat, the place where Zechariah pronounced the Benedictus, the Virgin’s spring, and the “desert” where the Baptist withdrew.

We have here proof that medieval pilgrims visited the same holy places that are visited today.

Church of the Visitation (Magnificat)

Saint John in the Mountains (birthplace of John the Baptist)

Saint John in the Wilderness (desert retreat of John the Baptist)

But, more importantly, Suriano gives us the name of this pilgrimage “the Mountains of Judah, called in Arabic Ayn el-Chermen (sic).” Thus, what the ancient pilgrims called Montana Iudae was undoubtedly this small village on the outskirts of Jerusalem that the Arabs call “Ayn el-Karem,” that is, the “Spring of the Vineyard.”

Between the two churches – the village church that commemorates the birth of the Precursor and the church on the hill that recalls the encounter between Mary and her cousin Elizabeth – there is a spring, the only one in the village. Both Christians and Muslims call it in Arabic “the spring of the Virgin”. According to apocryphal tradition, at this spring, Mary used to wash the diapers of the baby John.

By Henri Gourinard

Mary’s Spring