The armies of the Philistines and Israel stare at each other sternly. The Valley of Elah separates them. From the Philistine ranks, a gigantic soldier steps forward. He advances towards the front lines of the Israelite army to issue a challenge. A heavy silence falls over the camp of Israel, as no one dares to accept the challenge; the stature of the Philistine champion is that imposing. The Bible describes it as follows (1 Samuel 17:4-7):

“A champion named Goliath of Gath came out from the Philistine camp; he was six cubits and a span tall. He had a bronze helmet on his head and wore a bronze breastplate of scale armor weighing five thousand shekels, bronze greaves, and had a bronze scimitar slung from his shoulders. The shaft of his javelin was like a weaver’s beam, and its iron head weighed six hundred shekels. His shield-bearer went ahead of him.”

Left: “David and Goliath,” lithograph by Osmar Schindler (1888). Wikipedia

Right: Descending from Kh. Qeiyafa towards Emeq ha-Ela. The stream bed is marked by a line of terebinth trees (grey trees in the photo). Lior Peleh.

Suddenly, the voice of a youth is heard. David, son of Jesse, a shepherd from Bethlehem, offers himself for the duel. A short time before, he had entered the court of King Saul. There, he became friends with Jonathan, the king’s son. Initially, Saul tries to make David reconsider his suicidal project, but, facing such stubbornness, he accepts. Saul then orders David to be dressed in his own military equipment, but as expected, the helmet and the king’s armor are too large and cumbersome for the shepherd from Bethlehem. David sheds them, and sets off to meet Goliath, trusting in the protection of the Most High. As he crosses the stream, he picks up some smooth stones and puts them in his bag.

When David comes within range, Goliath insults him and all the army of Israel. David then rushes towards the Philistine, arms his sling with a stone, aims, and fires. The stone sinks into Goliath’s forehead, and he falls face down on the ground. Since he was not carrying a sword, David takes the dead man’s sword and cuts off his head. A wave of panic seizes the Philistines. Every man for himself! “Then the men of Israel and Judah sprang up with a battle cry and pursued them to the approaches of Gath and to the gates of Ekron, and Philistines fell wounded along the road from Shaaraim as far as Gath and Ekron.” (1 Samuel 17:52)

This is the dramatic plot of the most famous battle in the entire Bible. Now, what do we know about its geographical setting? Can we pinpoint its location with precision? Let’s return to the text for this. The biblical narrative opens with a description of the terrain chosen by the two armies, from Israel’s perspective, naturally:

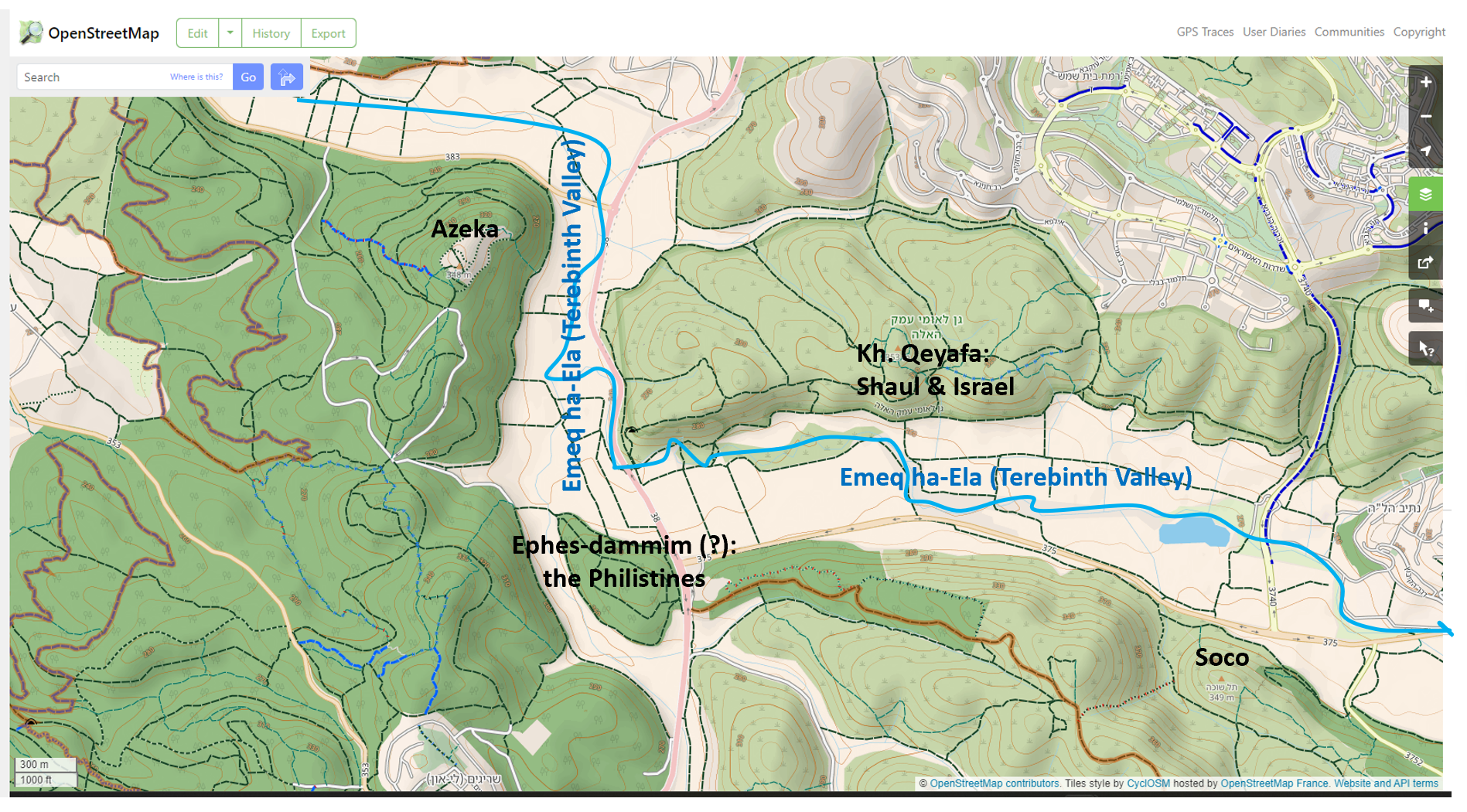

“The Philistines rallied their forces for battle at Socoh in Judah and camped between Socoh and Azekah at Ephes Dammim. Saul and the Israelites rallied and camped in the valley of the Elah, drawing up their battle line to meet the Philistines. The Philistines were stationed on one hill and the Israelites on an opposite hill, with a valley between them.” (1 Sam 17:1-3)

Map of the battle area. OpenStreetMap

The precarious position of the Israelites at the bottom of the Valley of Elah is striking, while the Philistines had time to choose a favorable terrain, atop the hills that stretch between Socoh and Azekah. Although the location of Ephes Dammim remains uncertain, by cross-referencing information with other passages of the Old Testament, we can identify Socoh and Azekah with a high degree of certainty. The latter also appears in extrabiblical sources like the Annals of Assyrian King Sennacherib, who besieged it in 701 BC. In David’s time, Azekah was probably under Philistine control. Socoh is less known. The sacred author defines it as a city of the tribe of Judah, to avoid confusion with another Socoh in the north. Its identification poses no further problem. A hill on the southern bank of the Elah stream preserved its name until recently. In Arabic, it is called Khirbet Shuweika (the ruin of Shuweika). It is worth noting that the Socoh in the north bears the same name. The similarity between the Arabic Shuweika and the Hebrew Socoh is evident. Now, the Israelis call it Giv‘at ha-Turmusim (the hill of the lupines) for the abundance of lupine flowers that bloom there at the end of winter.

View of the Valley of Elah (Emeq ha-Ela) from Giv’at ha-Turmusim photo by Henri Gourinard

Between Socoh and Azekah, the Valley of Elah (Emeq ha-Ela) takes a sharp turn to the north. Within this bend, a hill rises in front of Azekah. It was called Khirbet Qeyafa (the ruin of Qeyafa). At its summit, archaeologists found quite well-preserved remains of an Iron Age city, from the time of Saul, David, and Solomon. Khirbet Qeyafa features a wall open to the west and east by two gates. In Hebrew, gate translates to “sha’ar.” For this reason, several scholars have proposed identifying it with the Sha’araim of the Bible. Furthermore, archaeologists have demonstrated that the walls already existed in Saul’s time. We can imagine, then, that Saul set himself up behind its walls before sending his army to position themselves in the valley. In case of defeat against the Philistines, the city would have served as a refuge.

View of the Valley of Elah from Kh. Qeyafa photo by Henri Gourinard

God, however, granted victory to Israel. It was the Philistines who had to flee the battlefield. The survivors found their salvation behind the walls of the cities of Gath and Ekron.

By Henri Gourinard