With the week of Sukkot—the Festival of Booths, Cabanas, or Tabernacles—the cycle of holidays for the month of Tishrei (September/October) in the Jewish lunar calendar comes to an end. In Jesus’ time, as well as today, this was one of the major festivals, attracting thousands of pilgrims to Jerusalem, causing the number of people in the Holy City to multiply many times over. Back then, as now, Jews built booths where they lived for the week. In addition to being a celebration where the ancient Israelites offered in the Temple the first fruits of the land (bikurim), the significance of the Festival of Booths in the history of salvation lies in reminding the Jewish people of their nomadic origins before they entered the Promised Land.

“Then you shall declare in the presence of the LORD, your God, ‘My father was a refugee Aramean who went down to Egypt with a small household and lived there as a resident alien. But there he became a nation great, strong and numerous” – Deuteronomy 26.5

The first fruits of the land are featured during the festival of Sukkot via the decorations inside the booths—with garlands of fruit—and in the four species (arba’at ha-minim), which are traditionally used to bless the sukkah (booth). These include three branches: palm (lulav), myrtle (hadass), and willow (aravah), along with a citron called etrog. The historical dimension of the festival is reflected in the custom of welcoming guests (ushpizin) into the sukkah, just as Abraham received the three divine visitors under his tent during his wanderings in Canaan.

Young Jewish man praying at the Western Wall with the Four Species. (Wikimedia Commons)

We cannot be fully certain which of these symbols and customs were practiced by the Jews in the time of Jesus. What we can infer is that the surroundings of Jerusalem would have been filled with the booths of the diverse population of pilgrims. The Acts of the Apostles highlights the cosmopolitan nature of such crowds: for example, during the Feast of Pentecost (Shavuot)—another pilgrimage festival—in which those who were there to hear the Apostles came from across the Jewish diaspora:

“Parthians, Medes, and Elamites, inhabitants of Mesopotamia, Judea and Cappadocia, Pontus and Asia, Phrygia and Pamphylia, Egypt and the districts of Libya near Cyrene, as well as travelers from Rome, both Jews and converts to Judaism, Cretans and Arabs.” – Acts 2.9-11

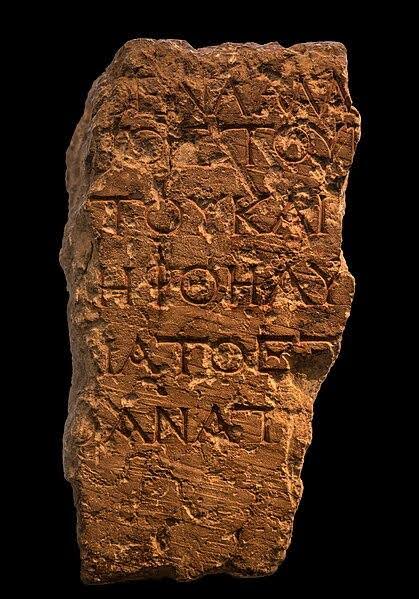

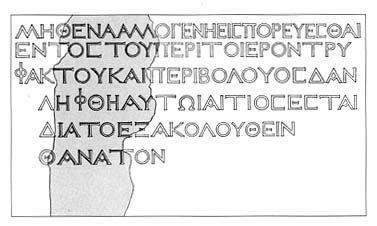

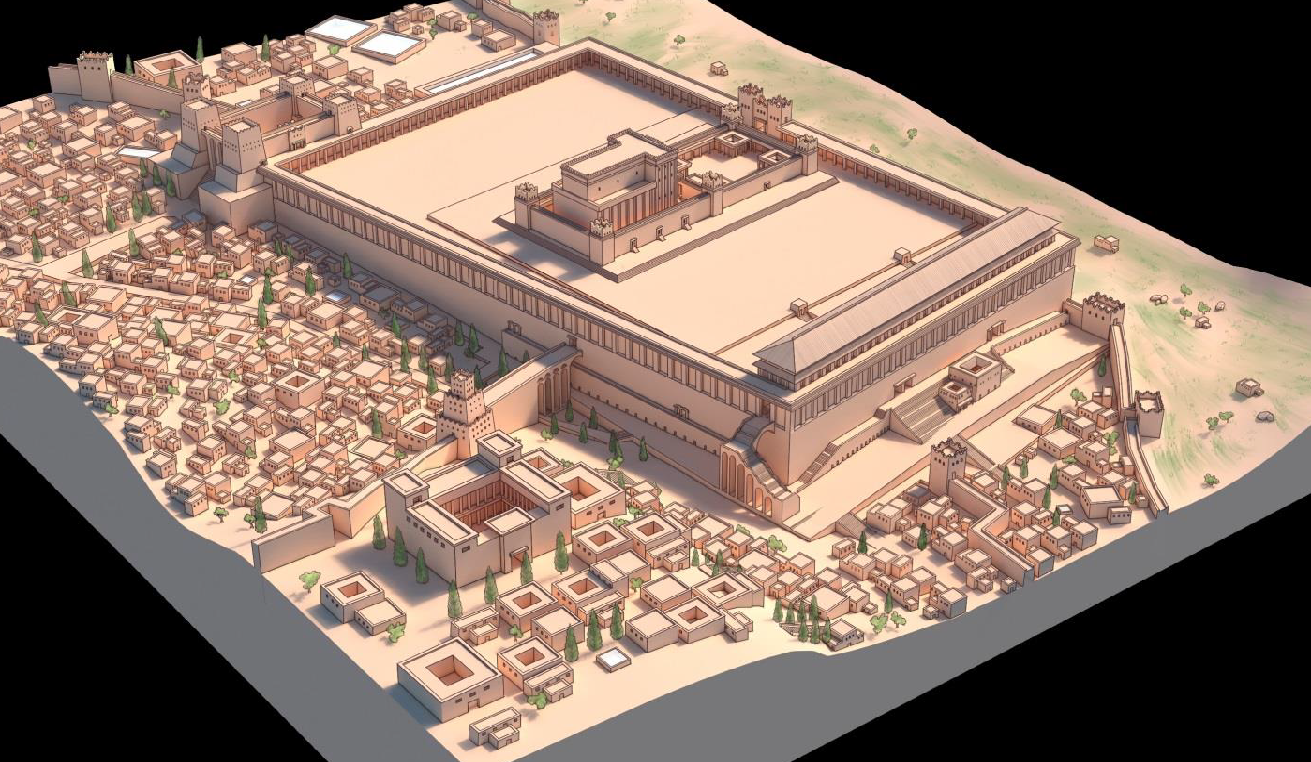

It was a mix of Jews, Gentiles, and proselytes. For this reason, in Herod’s Temple, inscriptions in Greek warned Gentiles—mainly Hellenes—not to enter the courts reserved for Israelites, under penalty of death. Although the Romans had stripped Jewish authorities of the power to carry out capital punishment, they turned a blind eye in certain cases of swift justice within the Temple precincts. This is evident in several instances when the crowds attempted to kill Jesus or in the stoning of Saint Stephen

No stranger is to enter within the balustrade round the temple and enclosure. Whoever is caught will be responsible to himself for his death, which will ensue.

The soreg, or barrier, in the Jerusalem Temple separated the “Courtyard of the Gentiles” from the “Courtyard of Women,” which was accessible only to Israelites (Saxum Visitor Center).

The Fourth Gospel devotes nearly four chapters to the Lord’s time in Jerusalem for that festival (John 7:1–10:39). In these chapters, Jesus delivers discourses of profound importance about His identity, mission, and unity with the Father. These teachings are interwoven with two significant episodes: the healing of the man born blind (John 9:1–34) and the story of the woman caught in adultery (John 8:1–12).

“Then the scribes and the Pharisees brought a woman who had been caught in adultery and made her stand in the middle. They said to him, ‘Teacher, this woman was caught in the very act of committing adultery. Now in the law, Moses commanded us to stone such women. So what do you say?’”– John 8:3-5

In the case of that woman, the accusation was not for profaning the Temple but for adultery. However, the intention of her accusers was not so much to judge the case but rather to test Jesus. The Master gave them a lesson in mercy: “bent down [He] began to write on the ground with his finger.” After a moment of uncomfortable waiting, Jesus “straightened up and said to them, ‘Let the one among you who is without sin be the first to throw a stone at her.’” (Jn 8:6,8) Ashamed, the accusers walked away, beginning with the elders.

By Henri Gourinard