After the Psalms, the Book of Isaiah is the Old Testament book most frequently in the New Testament. Its prophecies are explicitly mentioned ninety times, and implicit references exceed four hundred. This means that the early Christian preaching regarded this book as announcing Jesus Christ and the divine economy of salvation more clearly than any other prophetic writing.

For this reason, Saint Augustine stated that “[this prophet] then, together with his rebukes of wickedness, precepts of righteousness, and predictions of evil, also prophesied much more than the rest about Christ and the Church, that is, about the King and that city which he founded; so that some say he should be called an evangelist rather than a prophet” (The City of God, 18,29,1).

For his part, Saint Jerome regarded this book as a compendium of all Scriptures, stating: “I shall expound the book of Isaiah, showing that he was not only a prophet but also an evangelist and an apostle. … No one should think that I intend to summarize in a few words the contents of this book, since it encompasses all the mysteries of the Lord: it predicts Emmanuel, who will be born of the Virgin, will perform marvelous works and signs, will die, be buried, and rise from the realm of the dead, and will be the Savior of all nations” (Prologue to the Commentary on Isaiah).

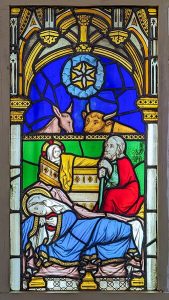

For this reason, the Book of Isaiah also holds a notable prominence in the liturgy. During certain moments of the liturgical cycle, such as Advent or Christmas, Isaiah accounts for almost three-quarters of the prophetic announcements from the Old Testament. It is no surprise, then, that iconography has often illustrated the mystery of Christmas with elements drawn from this prophetic book. This is evident, for example, when an ox and a donkey —mentioned in Isaiah 1:3 but not in the Gospel — are depicted in the stable at Bethlehem where Jesus was born

Nativity Scene Thomas Willement c.1845. From Holy Trinity Church, Carlisle

Prophet Isaiah, Sistine Chapel

The Prophecy of The Emmanuel

One of the most well-known passages from the prophet Isaiah is the one recounting his dialogue with King Ahaz of Judah when the king expresses his doubts about whether to join a coalition with the king of Damascus and the king of Samaria. They were pressuring him to align with them to jointly confront the threat of an Assyrian invasion.

Isaiah’s response to the king emphasizes that he must trust in God and have faith in His word, avoiding reliance on political alliances. The prophet offers, on behalf of the Lord, to provide a sign, but the monarch refuses. Nevertheless, Isaiah insists: “Therefore the Lord himself will give you a sign; the young woman (in the Hebrew text ‘almah, maiden) pregnant and about to bear a son, shall name him Emmanuel” (Isaiah 7:14, USCCB).

The prophet’s words, in their historical context and literal meaning, must have been quite clear to the protagonists, as in fact the king did not join that coalition. However, as words spoken on behalf of God, they also had the capacity to take on deeper meanings. This is what has happened with this and other prophetic texts in the progressive unfolding of Revelation.

The mother is a young woman, that is, a maiden who has not had children before. This could refer to the young wife of Ahaz or an unspecified young woman. In any case, by presenting her pregnancy as part of a sign given to the king, it is clear that we are witnessing something extraordinary. It is not surprising, then, that later interpreters — especially those who translated this text into Greek around the 2nd century B.C. — chose to translate the Hebrew word ‘almah, “maiden” with the Greek word for “virgin” to emphasize this remarkable novelty. Subsequently, the evangelists Saint Matthew (Matthew 1:23) and Saint Luke (Luke 1:26-31) indicated that Mary’s virginity was the sign that her Son is the Messiah, the true God-with-us, who brings salvation.

The child is also a significant element. If, as might be possible, the prophecy refers to the son of Ahaz, the future King Hezekiah, it would signify that his birth was a sign of divine protection, as it would secure the dynastic succession. If it refers to an unspecified child, the prophet’s words would have taught that the birth of this child would manifest the hope that “God is with us.” In the New Testament, these words are fulfilled in their deepest sense: Mary is both Virgin and Mother, and her Son is not merely a symbol of God’s protection but the very reality of the true God dwelling among us.

The name “Emmanuel” is a prophetic expression of the revelatory nature of the child’s birth. In the New Testament, the name emphasizes the joyful reality that Jesus is truly “God with us.”

The fact that the oracle was pronounced in specific historical circumstances does not limit its more transcendent, that is, messianic, horizon. This horizon has unfolded in the light of salvation history, in which events must be understood in relation to God’s saving plan and its ultimate fulfillment in Jesus Christ. Only from this perspective can one understand that the history of the Old Testament, both as a whole and in many of its stages, serves as a prophecy of the New Testament—a “preparation for the Gospel.” For this reason, in Christian reading, which in a sense benefits from knowledge of the “end,” the messianic interpretation of the oracle of Emmanuel is perfectly consistent with its literal sense.

Church of the Nativity, Bethlehem

The words of the prophet, fulfilled in Christ, have inspired numerous profound spiritual interpretations. Origen reflects: “This Emmanuel, born of the Virgin, eats butter and honey, and asks each of us for butter to eat. … Our sweet deeds, our gentle and good words, are the honey that Emmanuel, born of the Virgin, eats. … Truly, by partaking of our good words, deeds, and thoughts, He nourishes us with His spiritual, divine, and superior foods. And from the moment it is a blessed thing to welcome the Savior, with the doors of our hearts open, we prepare for Him the ‘honey’ and all His supper, and thus He Himself leads us to the great supper of the Father in the kingdom of heaven, which is in Christ Jesus.” (Homilies on Isaiah, 2.2).

By father Francisco Varo Pineda, priest